Regardless of the current weather transpiring outside of your window in your corner of the world, global climate change has occurred. According to the National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA), 2016 set a record as the warmest year on record and 16 of the 17 warmest years since 1880 have occurred since 2001. Winters have been growing shorter, sea level has risen as a result of melting land ice, and droughts and floods have become more severe over the course of the last century. These trends are projected to continue and intensify if greenhouse gas emissions continue to increase. And yet, last year, humankind set a record for the highest annual CO2 emissions ever.

Naturally, these changes are having an impact on the world's fish and wildlife. As species struggle to keep up with climate change-driven habitat loss, the range diffusion of pests and diseases, and the shifts in timing of natural events (like the blooming of trees and flowers, or the availability of food in the form of hatched insects), scientists believe that they will be forced out of their native habitats and into inhospitable terrain.

But, amidst this mountain of grim projections and reports, for residents of the southeastern United States, there's a glimmer of hope.

A 2014 paper that reports on a portion of an eight-year study conducted by The Nature Conservancy analyzed 237 million acres across the southeastern states for areas with the capacity to adapt to climate change while maintaining diversity and ecological function. Specifically, climate change strongholds were identified among the high elevation forests of the southern Appalachian Mountains.

"The kind of sites we identified were those with a complex landscape that contained a lot of micro-climates—mountains, valleys, slopes, caves, et cetera," said Mark Anderson, one of the authors of the report and the Director of Conservation Science for The Nature Conservancy. Such landscapes will allow slow-moving species like plants and amphibians to adjust to a changing climate by moving up or down in elevation to find a suitable microclimate, as opposed to hundreds of miles in latitude.

More Like This

The study also evaluated sites based on permeability—the presence of roads, pipelines, and other barriers to movement within the site—and contiguity with other strongholds. Both of these criteria were present in the southeastern sites, largely because of their occurrence on federally protected lands.

However, the dense array of micro-climates found in the southern Appalachian landscape also provides partial protection to species that are immobile or that are restricted in geographical movement.

For instance, dated research has suggested that, by the end of the century, the projected rise in global temperature would restrict native brook trout populations to only the highest reaches of headwater streams in southern Appalachia. But a recent study by the U. S. Forest Service (USFS) and U. S. Geological Survey took a more dynamic look at the relationship between air and water temperatures to find that, though streams with a relatively large drainage area and a gentle slope may warm in congruence with air temperatures, the temperatures of streams with adequate overhead canopy, high overall elevation, and a steeper gradient are much less sensitive to changes in air temperature—a good thing for coldwater fish in a warming world.

Other regions don't benefit from these buffering mechanisms. The region in which Arizona's native trout, the Apache trout, inhabits, for example, though somewhat diverse in elevation, will face powerful and sustained drought conditions in the next half-century if climate predictions continue on their current trajectory. According to a USGS study, increased average air temperatures threaten not only drought, but also an increased risk of forest fires, which remove shade cover and bank stability, resulting in more sediment in the streams, lower and warmer water, and habitat that is generally uninhabitable by trout.

While the Nature Conservancy study offers a measure of optimism for Appalachian ecosystems and their people, it is a momentary one. What it does not offer is an excuse for complacency. "Unfortunately," said Anderson, "there will be many species that will not be able to relocate as climate change makes their neighborhoods unlivable." Specifically, in the southern Appalachians, several tree species, like the red spruce, could face local extinction in a warmer world because they are already restricted to the highest mountain elevations. "That is why the ultimate goal is to reduce greenhouse gas emissions and stop climate change impacts from worsening," said Anderson. "Until that happens, these resilient landscapes offer a much needed safety net to allow many species to survive, interact and ensure healthy natural systems."

And there are additional threats to these climate change strongholds that must be heeded. An influx of pollution from mining, natural gas fracking, and development in these resilient landscapes threaten the existence of healthy natural systems and the clean water and natural resources they provide, which will become increasingly valuable if current climate predictions transpire. If they do, a significant number of people will be displaced by droughts and floods and forced to move inland.

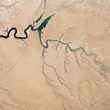

One climate prediction by a NASA study published in 2015 suggests that, if carbon dioxide emissions continue to increase on their current trend throughout the remainder of the 21st Century, it's likely that a drought worse than the Dust Bowl of the Great Depression era will grip Central America, Mexico, and the southwestern and Great Plains states and last for more than three decades, forcing a migration of people from these regions into more hospitable climes. However, if we take action to level off greenhouse gas emissions now, the chance of a mega-drought sits at a lowly 12%.

Further research has estimated that, due to projected sea level rise, as many as 13.1 million Americans could be displaced from their homes by the end of the century, and many of them will be fleeing areas adjacent to central and southern Appalachia. An independent study utilizing Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) data found that 20 of the 25 U. S. cities most vulnerable to coastal flooding by 2050 are in Florida. New York City; Charleston, South Carolina; Norfolk and Virginia Beach, Virginia, and Boston, Massachusetts finish out the list of cities that will see millions displaced. These climate refugees will likely move inland, and with the rest of the country steeped in drought, nearby areas of relative climate resiliency, such as southern Appalachia, top the list of places to settle.

Faced with a growing number of people inhabiting a reduced space, land-use conflicts will arise, and governments may be forced to sell off public lands to satisfy housing and resource demands. In following, development, natural resource consumption, and the resulting increase in pollution will likely place further strain on the Southeast's naturally resilient landscapes, effectively nullifying the opportunity to protect an important ecosystem in the face of climate change.

Even given the natural resilience of the southern Appalachian Mountains, in order to minimize the damage done to our ecosystems by climate change, both directly, and via the vast numbers of refugees it creates, we must work to rein in greenhouse gas emissions. Global climate change is not a local issue affecting only those physically displaced by nature. It is a global issue that is and will continue to have predictable and unpredictable effects on every corner of the planet and its inhabitants. Provided the opportunity to preserve and protect our valuable natural resources, it would be foolish to squander it in complacency.

Comments