A new article authored by a host of university-based biologists and environmental interests takes direct aim at public lands livestock grazing in the West, and claims it represents the “most common threat” to iconic American landscapes during a time of converging environmental crises.

The article, published in the journal BioScience, recommends three clear action steps that need to be taken in order to restore biological order and “rewild” the American West. They are:

- Retiring federal grazing allotments on 11 “reserves” across the West

- Reintroducing gray wolves on those reserves

- Reintroducing North American beavers on suitable habitat across those reserves

“These three rewilding steps could greatly improve ecosystem structure and function, especially in riparian areas,” the article reads.

The group of biologists, led by William J. Ripple of Oregon State University, chose wolves and beavers as the hinge species that would make rewilding possible. The group of biologists recommends wolf reintroduction across several western states. They say the absence of the apex predator is a great contributor to some of the West’s most pressing problems, like habitat degradation. For instance, in areas where wolves have been reintroduced, habitat across the wildlife spectrum has generally improved (even in the face of shrill opposition from the agricultural community and most hunters). The presence of wolves in Yellowstone National Park, for example, has forced elk to move around more and distribute themselves across more areas of the park rather than remain sedentary. This has resulted in improved grazing habitat across the park — areas that were once grazed to the dirt by stagnant elk now boast healthy browse, new aspen and willow recruitment and, as a result, more groundwater supplies.

Beavers, too, contribute to habitat improvement, particularly in riparian areas.

“By felling trees and shrubs and building dams, beavers enrich fish habitat, increase water and sediment retention, maintain water flows during drought, provide wet fire breaks, improve water quality, initiate recovery of incised channels, increase carbon sequestration, and generally enhance habitat for many riparian plant and animal species,” the article reads. It also notes that while suitable habitat for beavers only amounts to about 2 percent of the public lands estate, beaver activity benefits 70 percent of wildlife species in the West.

There’s no doubt that the group’s wolf reintroduction proposal will elicit pushback. Ever since wolves were reintroduced into Yellowstone National Park and parts of central Idaho and western Montana in 1995, political opposition has remained fierce and state fish and wildlife agencies have pushed the envelope on wolf management, allowing liberal hunting that, at times, has spurred the intervention of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to ensure the animals don’t go extinct a second time (wolves were largely eradicated in the lower 48 by the 1950s).

“Currently, wolf management by some of the western state governments is geared toward reducing their numbers, and it is essential that these policies be reversed and federal protected status be fully restored,” the article reads.

That said, wolves also have passionate advocates — in 2020, voters in Colorado directed the Colorado Parks and Wildlife Commission to develop a plan to reintroduce and manage wolves in the state. That plan is due by the end of 2023.

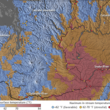

According to the biologists behind the article, wolves are considered vital to the rewilding effort “because their recovery and persistence require large areas.” By examining contiguous public lands that contain “core wolf habitat” and are at least 5,000 square kilometers, the article’s authors created what they call the Western Rewilding Network. This “network” stretches from southern New Mexico to northern Montana and west to California’s Sierra-Nevada Mountains. In all there are 11 “reserves” within the network and it encompasses 11 western states.

The Western Rewilding Network doesn’t just consist of land. It also categorizes 92 threatened and endangered species within the reserves, including 22 fish species, 11 mammals and dozens of amphibians, birds, insects and even crustaceans.

While the authors claim livestock grazing is the most serious obstacle to rewilding the West via the Western Rewilding Network (it’s problematic in 7 of the 11 proposed reserves, the authors say), they also recognize that mining, logging and oil and gas drilling also stand in the way of any such effort. But the solution to the grazing dilemma is the easiest. Canceling grazing leases would barely register on the national commodities market — only 2 percent of the nation’s meat supply comes from grazing leases in the West. Of note, the article’s authors only suggest the elimination of 29 percent of all livestock grazing leases in the West — they just support the cancellation of the leases within the proposed reserves. And, the authors note, there should be some sort of “economically and socially just federal compensation program for those who relinquish their government grazing permits … provided these allotments are permanently retired.”

“Livestock grazing is ubiquitous on federal lands in the American West and, astoundingly, even occurs within some protected areas, such as wilderness areas, wildlife refuges, and national monuments,” the article reads. “Federal lands with managed livestock allotments often have various ecological impacts because of the multiple direct and indirect effects of these introduced large herbivores. For example, in many areas, livestock grazing causes stream and wetland degradation, affects fire regimes, and inhibits the regeneration of woody species, especially willow.”

The article’s authors acknowledge that the Western Rewilding Network, should it ever be considered by the federal government (a very unlikely development even when viewed through the most optimistic of lenses during these politically charged and polarized times), its implementation will take time. But, they say, by removing offending grazing leases and bringing back the two mammals — wolves and beavers — that have the most dramatic positive impacts on the landscape, it could protect and restore the 44 threatened and endangered species most impacted by grazing leases.

“Although our proposal may at first blush appear controversial or even quixotic, we believe that ultra ambitious action is required,” the article reads. “We are in an unprecedented period of converging crises in the American West, including extended drought and water scarcity, extreme heat waves, massive fires triggered at least partly by climate change, and biodiversity loss with many threatened and endangered species.”

Comments