If you're a bamboo fly rod aficionado or would like to be but haven't been able to justify the lofty price tag that comes with bamboo, you can take a shot at winning on from the makers of the documentary Where the Yellowstone Goes. The filmmakers are giving away a custom made bamboo rod that was used in the film. Prizes in the contest include the rod, a Sweetgrass custom bamboo fly rod valued at $995, some copies of the movie's soundtrack on CD, and few other "goodies" donated by the contest's sponsors. If you're really intent on winning, participants who purchase anything from the online store before 12/25 will also receive an additional 5 extra entries for the giveaway.

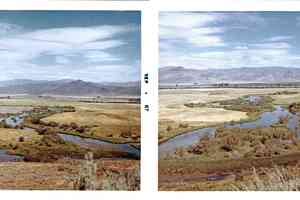

Where the Yellowstone Goes follows fishing guide Robert Hawkins and his small crew as they travel the Yellowstone River, the longest free flowing river in the contiguous United States. Director Hunter Weeks (10 MPH, Ride the Divide) illustrates the lives of various locals living in cities and dwindling towns alongside the Yellowstone, while exploring the history and controversies of the famous watershed. The film has been called "joyous to funny to heartbreaking" by the Huffington Post.