I’ve lost count of the number of eye-rolling stories that I’ve heard from guides about clients killing trophy fish caught from the West’s great trout rivers. The notion that a fish must die to appease the ego, it seems, is still richly embedded among a few trout anglers. And guides, well, they get to know a few trout anglers.

The dominant approach to fly fishing these days involves a catch-and-release ethos that’s borderline religious. But that’s not always the case, and “trophy hunting” isn’t just relegated to the gear guys and the hunting crowd. It’s also not limited to anglers of older generations with stronger ties to an “eat what you kill” mantra.

Even among us lift-the-pinky fly fishers, an insistence to pose with your trophy is still widespread. Sure, we’re not as big into wall mounts as our hunting brethren or the more long-in-the-tooth crowd, but, good grief, man, have you spent any time on Instagram? It’s gross, especially when you consider that a good number of the fish that “conservation-minded” anglers poke and prod and pose for the camera end up suffering the same fate, thanks to poor handling skills, as those that get bonked over the head. It’s not hard to spot the offenders — the grip ‘n grin selfie with a bone dry fish, trout hoisted sky high over a drift boat, fish laid on rocks or grass, spawning fish squeezed so tight by smiling anglers that their eggs squirt out, and so on. In half a century of fly fishing, I’ve likely done all of the above. The good news? I have learned to do better. So can everybody else.

Earlier this spring, as I sat in the bow of Jeremy DeVries’ “so choice,” hand-hewn wooden drift boat as we floated down the upper-middle stretch of the Bighorn River, a familiar tale was told. DeVries, a seasoned fly-fishing and waterfowl hunting guide from Billings, and now the proprietor at River Rock Lodge on the Bighorn, was regaling us with the story of a client who managed to latch into a real toad — a 30-inch Bighorn brown that, by sheer virtue of its weight, was able to plant itself at the bottom of an eddy and only came to hand with much cajoling and some advanced boat work.

“It was a beast,” DeVries told us. “An absolute monster. One of the biggest trout I’ve ever seen.” But then the story took a dark turn.

“I gotta kill it, Jeremy,” the client reportedly told his guide. “I’ll never catch another fish like this, and I gotta have it over the mantel.” Before DeVries could protest, his client had dispatched one of the biggest trout in the Bighorn by clocking its head on a riverside rock. Fiberglass mold be damned.

“Just like that,” Jeremy said, “it was over.” To his credit, DeVries struggled with the death of the behemoth. It bugged him for the rest of the trip. Then, pragmatism set in. There are lots of reasons he could have been angry at his client for taking the life of such a magnificent fish. But there were reasons, too, that helped him find his Zen that afternoon. Logic is a wonderful thing, and the realization that, on the Bighorn, big fish are in no short supply, played a role in his decision to just grin and bear it on behalf of his client.

“Oh, it could have been ugly,” DeVries said. “I mean, who kills fish anymore? Of any size? But that one? Who kills that one?”

Devries continued the tale and, even to the ears of a fairly staunch conservationist, the logic he espoused — and the logic that helped him make it to the takeout without drowning his client — made sense. First, he noted, he’s a student of the river, just like any good guide should be. And, in the spring, when the Bighorn’s rainbows are building redds and getting ready to spawn in the chilly, 41-degree water below Yellowtail Dam, DeFries has noticed something others might miss.

“Those redds are swept clean by female rainbows that might be 18 or 20 inches long, and the males that come in are about the same size, sometimes a little bigger,” he said. “You don’t see the really big fish on the redds. They just don’t have the energy.

“In the fall,” he continued, “the same is true for the browns. The females will build redds and the males will do what they do to get into position to spawn — and they’re big fish. But they’re not really big fish, like the one my client killed. We very rarely see those big fish on the redds. They’re old. They’re tired. They don’t spawn anymore, or, if they do, it’s very little. The younger fish have more energy. The bigger fish? All they do is eat.”

All of that computes. We’ve all heard of fish hatcheries possessing “brood” trout — really big fish they keep on hand just for spawning. Eventually, with age, those big trout will become less productive. The same thing happens in the river with wild trout — as they age, they become less active and reproduce less and less as time passes.

So, while Jeremy was tempted to let his client know that he’d just killed a trout that was a massive contributor to the Bighorn River’s gene pool, letting his thoughts percolate was the right call. Thanks to the client, the fish would never spawn again. But, chances were, it hadn’t spawned in quite some time. The only loss to the Bighorn? A giant brown trout that might have made another angler or two happy before it finally perished from the earth. A few more Instagram posts.

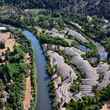

A tailwater for the ages

The Bighorn River — or at least the Bighorn River where it’s earned its stripes as a true trophy trout river as it flows out of the bottom of Yellowtail Dam in southern Montana — is legendary. Boasting prolific bug life, not unlike its tailwater cousin, the Missouri below Holter Dam, it’s home to some 6,000 wild trout per mile. This, alone, makes it a destination among destinations. The “drift boat hatch” starts sometime around the first week of May and lasts all summer long. It’s the cover charge anglers pay to listen to the Bighorn River Band, and, frankly, it’s worth it.

Truth be told, the Bighorn is fishable all year long — even during the frigid months of January and February on the high prairie. Its tailwater flows keep the river’s trout happy and healthy, and anglers can reasonably expect to have a shot at a trophy trout, regardless of what the calendar says. It’s a shoulder-season all-star. When other Western tailwaters are locked in ice — or at least require anglers to deal with bank ice that lines the river in mini-icebergs — the Bighorn is going to clock in as “fishable” in March and April (or in November and December). But, honestly, the river is at its charismatic best when everybody wants to be fishing: high summer.

Come June and July, and continuing through August and into September, the Bighorn makes sure that the anglers who descend upon it come away with the impression that they at least had the chance to land the fish of a lifetime. And make no mistake about it, the fish of every trout angler’s lifetime swims in the Bighorn. Catching it? Well, that’s another matter altogether.

If you fish the Bighorn in the summer, chances are you’ll have some high-quality dry-fly fishing on your hands. The river’s lowland location on the cusp of the Great Plains makes it a terrestrial-bug river — think big Chernobyls and hopper patterns. In the evenings, when the light gets low, I’d be very tempted to swing a Moorish Mouse if I found myself on the water.

When fall rolls around and the days get shorter, seasoned Bighorn guides and anglers will look for opportunities to swing big streamers through likely holding water. DeVries notes that, while the redd-building starts happening in late October on the Bighorn, the actual brown-trout spawn doesn’t take place until November or December. But as the weather cools and the days get a little shorter, the river’s browns get more aggressive. Predictably, during low-light periods of the day, a big, aggressive streamer pattern is a solid option.

And, of course, like most Western tailwaters, the dry-fly season tends to boil down to what can be epic baetis hatches. DeVries, who, by the time the Blue-winged Olives come out, is busy with duck hunters, can recall blanket mayfly hatches on blustery October and November days. And at that time of the year, the numbers of anglers on the river has drastically declined. A fall trip to the Bighorn? Highly recommended. And, if you’re an avid waterfowl hunter, a cast-and-blast trip is totally doable.

Stealing weather

We fished the ‘Horn in early April, and it was earlier than I would have preferred. But summer travel and a host of other commitments made April our only real choice. So, we buckled up — it could be miserable, or we could hit a nice little spring window and catch some fish. The latter wasn’t an issue — as I said, the Bighorn is an angler’s river. Catching fish isn’t usually a problem. Sure, it might turn off for a day. But two days? In a row? Highly unlikely.

And get lucky we did. We stole some weather from the summer that’s on its way — on our second day, the temps along the middle reaches of this fabled Western trout destination approached 80 degrees. We didn’t bother with waders — but wet wading was, to say the least, exhilarating. And the fish, like the weather, offered up a pleasant surprise.

As Jeremy pushed the boat downstream on our first bluebird day fishing from his River Rock Lodge, we were hoping for some early season dry-fly action. It wasn’t meant to be. While the outside temperature was ideal, the river, in early April, flowed out from beneath Yellowtail Dam at a crisp 38 degrees. Just a few miles downstream, it registered at 41 degrees. Nymphs were the order of the day.

Being a tailwater that gets fished hard and heavy most of the year, the Bighorn teaches its guides lots of lessons. The prolific sowbugs below the dam offer the river’s wild trout a veritable buffet of protein, and seasoned guides on the ‘Horn have boxes of flies tied to imitate this meaty little treat. Floated beneath an indicator and trailed with a heavy Perdigon, the pink-ish sowbug patterns were too ideal for the trout to resist. Would we rather have been dry-fly fishing? Sure. But the river picks the situation — we’re just spectators on any given day. And on this trip, dry-fly purists would likely have come up empty-handed. We chose to meet the fish on their terms. And I’m so glad we did.

In three absolutely beautiful days on the river, we landed more than a dozen fish over 20 inches, and we notched a beefy 23-inch rainbow and a stunning, perfectly proportioned 22-inch brown. I also managed to catch two 19-inch whitefish, as well. Variety is, indeed, the spice of life, and, lest you scoff, big whitefish aren’t slouches. Not at all.

Better yet, and, to Jeremy’s relief, every fish — even the trophies we managed to bring to the boat — made it back to the chilled waters of one of the West’s most storied tailwaters.

IF YOU GO

Getting there

The nearest airport is in Billings, and there are numerous direct flights to Billings from Denver, Minneapolis, Seattle, Salt Lake City and other Western hubs. In addition, for most folks in the West and Midwest, getting to the Bighorn is doable via car, especially if a good road trip sounds appealing.

When to go

The Bighorn is a very stable tailwater. It can literally be fished all year long. But, truth be told, for simple comfort and enjoyment and to prevent frostbite, the river is best visited from March through November. Spring and fall offer baetis hatches, but keep in mind, the river’s water some from deep at the bottom of Yellowtail Dam. It’s cold. And it stays cold for a good 30 miles downstream, all summer long. Summer terrestrial season (mid-July until the first hard freeze in early October) can be epic. Rainbows spawn in the spring and can be aggressive before they pair up. Browns and whitefish are fall spawners, with browns getting serious about redd-building in late October.

Choosing an outfitter

You won’t have any difficulty finding an outfitter on the Bighorn — there are several. While all provide lodging, guides and transportation to and from the river, others offer more affordable plans that include DIY cooking, etc. River Rock Lodge offers excellent lodging options in its main lodge, and, for smaller groups or carry-over groups, it also has a very nice A-frame cabin. Meals are not included in the lodge’s base package, but, for a premium, the lodge will bring a chef in from Billings to prepare meals.

Comments

John Heckert replied on Permalink

Pretty sure you meant Holter damn on the Missouri

Chad Shmukler replied on Permalink

Michael Wong replied on Permalink

Holter DAMN? Not DAM? Did I miss something?

steve replied on Permalink

Please post a recipe for trout that includes releasing the fish.

Instead of torturing a dozen fish and leaving them to die of exhaustion, I will catch one and eat it, thanks.

Kerry replied on Permalink

Instead of going to all that trouble with costly equipment and the hassle of catching them, you can buy them at the supermarket. Usually more tasty than the wild ones.

Michael Wong replied on Permalink

I really liked your article. I am so pained when I see people abuse a beautiful trout in order to get that hero shot. These days, I am teaching my buddies how to not even TOUCH the fish before releasing. Even brown trout that roll around the tippet and get 2 hook lodged while they are wrapped can OFTEN be released without touching. These days I average 60-100 hookups in highly pressured waters in Colorado, and so I. don't even try to land most of them unless they are truly epic fish. You know you have arrived if you don't need to prove yourself to anyone. There is another way you know. When you release a trout so gently that it swims back to same spot in the river. Then you catch it again 2 more times in the mouth within an hour.

Pages